A hint was made some time ago that a podcast was in the works. Well,

finally, it’s made its way into the world. It’s an odd little child

which will need time to grow and gain a form that will serve a role in

the contemporary Buddhist landscape. For now, it’s an experiment: an

attempt to share conversations between two long-term Buddhists that have

not been particularly good at towing the line and doing the normal

Buddhist thing. In this podcast we mix banter, uncompromising discussion

and down-to-earth enquiry on all manner of topic related to Western

Buddhism.

The first episode is short and sweet, offering an introduction to the hosts, the podcast and the direction we intend to take. It is only about five minutes long so it’s probably best considered a mini episode. There are now four episodes up and our first interview will go live very soon. There's been lots of interest and our episode on cults has really blown up.

The first episode is short and sweet, offering an introduction to the hosts, the podcast and the direction we intend to take. It is only about five minutes long so it’s probably best considered a mini episode. There are now four episodes up and our first interview will go live very soon. There's been lots of interest and our episode on cults has really blown up.

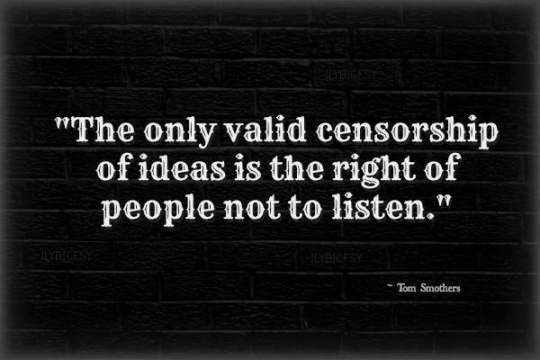

Ultimately, this podcast plans to go where other Buddhist podcast fear to tread. As non-experts, and not being Buddhist teachers, we enjoy the sort of freedom that lends itself to uninhibited discussion of the sorts of topics often avoided by others in the Buddhist world. As with any successful podcast project, it will be as much for our own pleasure and curiosity as for the wider community. There exists a clear line of tension between these two and we will explore that line as the series goes on. We hope that some of you will enjoy accompanying us as we explore and experiment. If you have suggestions on potential guests who are unknown, drop us a line.

Finally, for now, episodes can be listened to and downloaded from soundcloud. We also have a dedicated Facebook page and Twitter feed where comments can be made, criticisms can be given and compliments are welcome too. Enjoy.

Please note once more that all future postings will be found exclusively at: Post-traditional Buddhism